|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

World War 2 Nonfiction

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

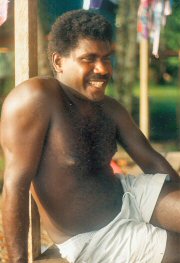

Terry Marshall. Chief Willie of Ughele Village, Rendova, Solomon Islands. |

Willie recounts this 1943 event as if he were rehashing this morning's sermon in Lokuru.

Wait a sec. Chief Willie's 52, only two years my elder. He was a toddler during the war. His tales memorialize his people's history, not his personal experience.

Back in Ughele, on Willie's veranda fronting the bay, the nightly feast far surpasses lunch in Lokuru. Radio joins us, grabs a barbecued coral trout. "At dawn, tide, moon, and weather will converge. Fish will run beyond the point," he says. Willie nods. We'll take his canoe.

Willie's son-in-law Raouli heaps his plate with fish and taro. "In America, do black men teach school?" he asks. He's a primary teacher, home for Christmas break with his wife, Chief's eldest daughter. "Of course," I say, and for an hour we talk race, politics and history. Pastor joins us. Village men I've not met glide into vacant spaces on the bench lining the veranda, blend instantly into the ongoing stories. One regales us with a tale of a youthful pig-stealing sortie, or was it a raid on a Japanese rice cache? Time seems suspended in these stories, irrelevant.

|

|

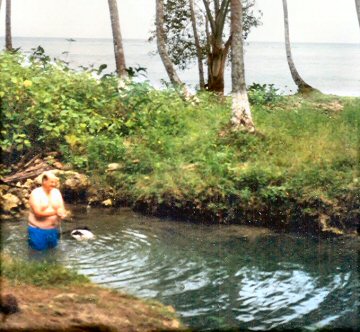

Terry Marshall. Raoli of Ughele Village, Rendova, Solomon Islands. |

Willie says a Japanese tuna boat will dock tomorrow or the next day at Ughele wharf. Welcoming plans emerge over mounds of four-inch-long pan-fried fish. Somehow, we drift back into 1943. Willie leads us as we rescue a downed American pilot. We paddle all night through enemy-infested seas, and sigh with relief as torrential rain gives us cover. We ambush Japanese patrols. We signal up and down the coast, warning of bomber waves zeroing in on Guadalcanal--all the while nibbling from bowls and platters on the picnic bench that serves as Willie's dining table. No alcohol loosens our tongues or dulls our minds. Seventh Day Adventists don't drink.

Night wears on. I slip away to my bedroom, adjacent to the veranda. The story-tellers dwindle, until, finally, voices cease. I lie awake inside a tent of white mosquito netting, my mind buzzing with today's events. Willie's stories bring World War 2 to life. Yet, his unmasked pride in killing repudiates his pious sermon in Lokuru. No wonder he led "Onward Christian Soldiers" with gusto. He's a soldier reveling in his exploits. No, wait--he's reveling in his father's exploits.

I flip on my flashlight, prop it against my camp pillow so I can scribble today's notes into my journal. No one wears a watch in Ughele. Mine reads 11:42 p.m. Like time, dates have no meaning here. My journal tells me otherwise: today was December 7, 1991. Fifty years ago to the day, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and yanked America into World War 2. Today, in Ughele, Rendova, Solomon Islands, World War 2 lives on, as surely as if it were fought last week.

Village life: Not what you think it is

|

|

Terry Marshall. Ughele primary school, Rendova, Solomon Islands. |

Several days pass. Late in the afternoon, I close the four-room primary school, padlock the one lockable room. I'm beat. A rancorous staff meeting unmasked a festering feud among our Pidgin teachers, Solomon Islanders all. For two hours, we yammered over one teacher's incessant complaints: no one works as hard as she; she lacks this, and that. The barrage of Pidgin has given me a headache. I head for the village bathing pond to wash away the stains of verbal battle.

|

|

Terry Marshall. Main street Ughele, Rendova, Solomon Islands |

For the quarter mile from school to Chief Willie's house, Ughele's "main street" is two parallel dirt trails through foot-trodden field grass, as if wagon trains once passed through. Yet, there are no cars, no trucks, not even a bicycle or wheelbarrow, no beasts of burden in Ughele.

The only sound is my sandals scuffing through field-grass. No radios. No TVs. No phones ringing. When I stop, silence. In the distance, a child laughs, a woman's muted voice responds. The sounds fade. Wild shrieks shatter the quiet. A band of blazing colors screeches through the tree-tops: parrots. They alight, fall silent. I walk on. No dogs nip at my heels or bark when I pass.

An outboard engine echoes across the bay. I locate it, a distant shadow against the reflected sun. Chief Willie could tell me who the canoe belongs to and who's driving. He knows each engine by its whine, each driver by the canoe's movements.

The grass dies out beyond Willie's, and the path widens. The concrete wharf is fifty feet to the left. Here Ughele congregates on Monday mornings around a horseshoe of wooden stalls to sell produce to passengers on the inter-island ship, Iuminao, when it pauses en route to Gizo from Guadalcanal. Now the stalls are deserted. Late tonight the arena will buzz with milling teenagers when, sans food, drink or souped-up cars, these stalls serve as Ughele's Sonic Drive-in.

|

|

Terry Marshall. Ughele wharf, Rendova, Solomon Islands. |

A half-mile from Willie's house, the path narrows to footprint width. I tightrope across the makeshift bridge, a pair of palm logs, over a small creek that marks the village's eastern boundary and arrive at the stream with its sauna-sized natural pool where most village men and children bathe. Usually it's Rocky Mountain spring clear. This evening I'm late, the water murky.

|

|

Terry Marshall. Bathing pool, Terry Marshall not pictured. |

Like most Solomon Islands communities, Ughele violates the American image of a proper village. Even with 1,000 residents--huge by Solomon Islands standards--Ughele has no business district, no plaza anchored by church and government office, no cantina. No malls, cafes, social clubs or sporting events provide diversion. No movies offer escape. I can't wander down to the post office, or buy a Coke at the general store. Ughele has neither. Ughele is a mile of thatched huts winding along the bay in two zig-zag rows.

Chief houses me in relative luxury. I sleep on a foam pad atop a raised wooden platform. Willie's compound has a water-seal pit toilet, built for our arrival, but I'm the only one using it. Villagers use designated areas in the open near the beach. Chief has a diesel-powered generator, and our house alone has electricity--a couple of hanging light bulbs, no refrigeration. Our house has a tightly thatched roof and walls, hard-packed dirt floor, cut-outs for windows and doors.

Chief's veranda is the center of adult Ughele's social life. An ever-shifting assembly of men provides fellowship. Tonight I last until 11:30 before the repetition of familiar stories and small talk wears me down. I listen from my bunk. Finally, words blur, and I drift off.

2:12 a.m., awake again. The blessed light zeros in like an interrogation lamp. Willie, wearing only frayed walking shorts, no shirt, sleeps without pillow, padding, or mosquito net on the hardwood bench that borders the veranda and sea wall. I wrap on my lava-lava, slip into the main room, unplug the lights. Night engulfs us. The generator drones on. Sometime in the night someone turns it off, or it runs out of petrol. Willie's gone at 4:33 when I awake again.

War images illuminate combat fatigue

Christmas morning, 1991: no rats yet, but for the sixty-seventh night running some unknown force jars me awake long before dawn. This morning, 2:57 a.m.

Ultimate Language Secrets

You've learned about Walkabout language learning. Want more ideas about how to learn languages faster and easier? Owen Lee is an expert language learner; he speaks half a dozen languages. He gives you tons of language learning ideas in Ultimate Language Secrets.

Leslie, at Your Language Guide has read this book and she thinks that it has fantastic ideas about language learning. Plus, we love the free Beyond Languages book that he includes. Read the full review.

The tropics should mean carefree sleep. Palm fronds rustle outside my room. Rendova Bay laps gently twenty feet away. A white net shields me from the malaria-laden mosquitoes, but equally as important, from rats. They dash along the hand-hewn rafters as if beams were catwalks to battle stations. They bash about like drunken sailors, squealing, roughhousing, leaping. I have yet to sleep more than two hours at a stretch since I arrived in the Solomons nine weeks ago.

Wide awake in the dark, eerie images overtake me. A snap, a muffled voice: a commando skulks outside, any moment to burst into the room, stiletto flashing. An eerie squeak: rat? bat? a signal to attack? The enemy parrots jungle sounds, you know.

My mission to Rendova is for the Peace Corps, but war dominates my thoughts. Are these visions Chief Willie's stories coming back to haunt me? My own imagination gone berserk?

In July 1943, across the channel beyond Willie's veranda, raw GIs on New Georgia faced a similar night huddled in foxholes, not beds. The jungle spooked them: shadows, faint sounds, nothing at all. A panicky GI fired a shot. Terrified men popped from their foxholes to pepper the black jungle. In one week, the U.S. Army evacuated 360 jittery soldiers to Guadalcanal. That incident spurred research that identified combat fatigue--"war nerves." The men snapped under strain and exhaustion and intimidating jungle. Most of those soldiers were younger than the thirty-two American Peace Corps trainees with me in Ughele.

We Peace Corps have been in Ughele only 24 days, but complaints mount. Cold fish and yams no longer make a quaint breakfast. Drought continues and sections of the village have no water; the volunteers and their host families must haul it from the stream for cooking. The water-seal pit toilets promised by Chief Willie haven't been built. They're tired of trekking off to a feces-strewn beach to relieve themselves, or to change a tampon. Classes drag on. The first-blush judgment that Pidgin is mere baby-talk English has been rudely shot down as we teach subtle forms needed to express doubt or anticipated action. Trainees and staff form cliques. Rumors flourish as if sprouted from magic beans. Sore throats, sunburn, diarrhea sap energy, and coral scrapes set nerves on edge. Three trainees contract malaria. Irritations fester. Christmas dawns in tropical heat, without mall Santas or decorated trees. Yet, I find myself feeling more sympathy for the fears of those frightened soldiers on New Georgia than for the complaints of my own charges.

First-person experiences with a World War 2 hero

This week's mail brought an unexpected package from a World War 2 veteran, Col. George Tuck. He'd called me after reading my article about Solomon Islands war hero Jacob Vouza in Retired Officer magazine, and he and I had discussed writing a book together about the war on Guadalcanal when I left for this assignment in the Solomons.

Tuck arrived in the Solomons with a glider squadron in mid-1943. By then, Guadalcanal was a staging base, not the battlefront, and Tuck had free time aplenty. A farmer from Oklahoma, he sent for seeds from an uncle. He gardened. He explored the island. He met Solomon Islanders.

|

|

Courtesy George Tuck. Sir Jacob Vouza and Col. George Tuck, ca. 1943, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. |

Tuck's package includes a dozen photos from 1943: bomb-shredded palms barren as scarred telephone poles; shirtless GIs with two Solomon Islanders, all stiffly unsmiling, as if facing a Matthew Brady field camera; a downed Japanese bomber, GIs posed at nose and tail as if each personally had shot it from the sky. The prize photo is young Tuck, a swaggering pilot with shoulder pistol and pith helmet, beside a muscular 45-year-old Jacob Vouza, with M-1 ready.

Vouza was a bona fide war hero before Tuck met him. The Japanese captured Vouza, an allied scout, early in the war. When he refused to talk, they tied him to a tree, bayoneted him, slit his throat, and left him to die. Vouza chewed through the rope, then crawled and stumbled miles through jungle and raging battle to report enemy positions to his company commander.

Tuck and Vouza became friends. A marksman with a rifle, Vouza one day pointed to Tuck's .45 and asked to fire it. "After a few clips he was a good shot. A few more, and he was an expert," Tuck recalls. Fascinated by airplanes, Vouza asked Tuck to take him flying.

"Can't," Tuck said. "Against regulations."

Vouza insisted. Tuck flew him on his first air view of Guadalcanal, filing his flight plan as a solo training jaunt. Next day, Vouza returned: "Take me again. I will jump out."

"He was fearless, but I couldn't go that far," Tuck said.

"Another afternoon, a buddy and I strolled off to a creek to bathe. From nowhere, a shot rang out. We high-tailed it out. Later, we told Vouza about it. He took off and returned a couple of days later with a bloody gunny sack. 'Jap fella no shootum at fly boys no more ever,' Vouza told us. We didn't have the stomach to look inside the sack."

I knew Jacob Vouza as an old man in the late 1970s, white haired, slow of foot, hard of hearing. He would come to the Peace Corps office in Honiara, the capital city, when he needed a ride home. His village--California--was twenty miles by washboard road and jeep trail up the Guadalcanal coast. He believed America remained his staunchest ally. I often drove him home.

Tuck's photos remind me of one I found in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.: a gang of GIs and nurses piled on a Willys jeep at a Guadalcanal river, hamming it up like college kids on spring break. I compare it to my own snapshots of Peace Corps volunteers on weekend outings. Trade the Willys for a Suzuki. Substitute shorts and T-shirts for khaki dungarees. Let crew cuts sprout into shaggy mops. That 1943 shot could easily be 1979 or 1992. I suspect the ceaseless carping of PCVs sounds much like the endless griping of GIs.

|

|

National Archives, Washington, DC. World War 2 GIs and nurses, Solomon Islands. |

More war images: Conjuring up JFK and PT-109

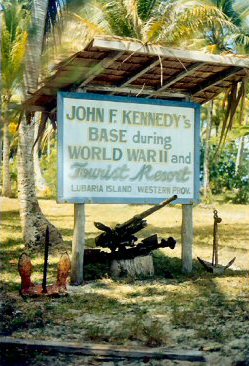

I'm compelled by Tuck's photos and Chief Willie's war stories to organize an excursion to Lumbaria Island, ninety minutes west of Ughele in Chief's enormous motorized dugout. In 1943, Lumbaria had been an American P-T (patrol torpedo boat) base. Lt. (Junior Grade) John F. Kennedy was stationed there.

|

|

Terry Marshall. A sign welcomes visitors to Lumbaria Island, Rendova, Solomon Islands. |

We pack a picnic lunch before we go. Someone scrounges up a hand of bananas and a fresh pineapple. Two of us go shopping. The only woman in the village who bakes bread has sold her day's supply, so we search out a store to see what we can get. No signs identify Ughele's four stores--no hand-scrawled Joe's Tienda, no advertisements for Coca-Cola, no Open/Closed signs. Each is merely a window-front on its owner's thatched hut. I locate a store. It sells only a score of basic items: tinned tuna, matches, Navy biscuits, fishing line, three aluminum pots. We settle for a bundle of concrete-hard Navy biscuits and several tins of Solomon Blue tuna, the inexpensive grade of choice among PCVs, a grade sold as cat food in the U.S.

Lumbaria Island is uninhabited, but a weathered sign confirms that President Kennedy lived here. Lumbaria is what World War 2 should be in the 1990s: shards and scraps. I photograph a rusted machine gun planted like a lawn ornament beside the sign, and tromp among slivers of cement pilings. The island has a war museum: a windowless one-room leaf hut. It's padlocked. Little else attests to that fifty-year-old war--a length of rusted pipe, man-made depressions here and there. No docks. No decrepit buildings. We conjure up images of JFK and his crew tying PT-109 to a now-phantom dock. Not far from here, in August 1943, Biuku Gasa and Aaron Kumana paddled Lt. Kennedy and his PT-109 crew to safety. Today's Lumbaria presents none of Hollywood's drama. Nor does it give me any clues as to why the war lives on here.

We speed home in a driving squall. We're drenched in thirty seconds. I'd forgotten how cold tropical rain can be, and I recall Robert Leckie's war memoir, Helmet for My Pillow:

The rainy season was upon us ... whole days of downpour when I lay drenched and shivering, gazing blankly out of my hole, watching as the sheeted gray rain whipped and undulated over the Ridge. At such times, a man's brain seems to cease to function ... one is aware only of life, of wetness, of the cold gray rain.

War haunts the present

|

|

Terry Marshall. World War 2 relic; an old tank rusts in the jungle of the Solomon Islands. |

En route back to Ughele, benumbed by the rain, my mind takes me back to the war, back to my earlier stay in the Solomons.

In 1977, before we moved to Honiara, the Solomons to me meant Guadalcanal--an old newsreel of exhausted Leathernecks slogging single file like pack mules through steamy jungle; Sherman tanks foundering in hip-deep mud; John Wayne rallying his men for another assault. Like Victory at Sea, Guadalcanal seemed a faded video, an era long gone--my father's generation.

I realized quickly World War 2 hadn't faded away. Guadalcanal was a great game park, inhabited not by the wildebeests and lions of Africa, but by rusting hulks of the predators of war.

It's 1978. Machete in hand, I slash my way three meters off a path in the jungle. A crumpled fighter plane leers from its vine-woven mausoleum. From the movies, I had a more dramatic image: a P-38 dives into battle, guns blazing. It twists, turns, eludes; the enemy pursues him. Tell-tale smoke puffs out. Another Zero flames into the sea. We always won in those movie dogfights. In the real-life Guadalcanal campaign, America lost 615 planes; the Japanese, 682.

But this relic suffers no bullet holes, no fire-scarred engine, no blasted wing. This pilot simply didn't make it back to Henderson Field. Did he run out of fuel? Did some make-shift part fail? I imagine the downed pilot, led by Jacob Vouza, creeping back through Japanese lines, returning to battle in another craft.

Mid-1979: I'm trudging through chest-high nila grass (needle grass--it can shred pants) down the side of a ridge above Henderson Field, trying to find a path to the Lungga river. Suddenly, I'm face to face with an unexploded bomb. I inch away on cat's paws.

Early 1980: heaped shell casings and rotted C-ration cans like shabby grave markers lead me to a GI foxhole on Bloody Ridge overlooking Henderson Field. I jump in, imagine mortars homing in, machine-gun fire.

John Hersey joined the Marines' H Company on Guadalcanal in 1942. They hiked this ridge. He writes in Into the Valley:

The first thing a green man fixes upon in his mind is the noise . . . Its constant fabric was rifle fire . . . like a knife tearing into the fabric. . . . The noise of the mortars was . . . a thump which vibrated not just your eardrums, but your entrails as well . . . dive bombs fumbling into the jungle, the laughter of strafing P-39s . . . the soft, fluttery noise of our artillery shells making a trip. The noise alone was enough to scare a new man . . .

November 1991: before coming to Ughele, I spend a month in Honiara. On a hot, lazy Sunday, thudding explosions like echoes from long-departed American guns jolt me back into my father's war. Wartime puffs of smoke curl over Bloody Ridge like a smoke signal from history.

Fifty years after America liberated the Solomons, torrential rains still flush bombs from their tombs. Scorching sun bakes them. They erode in tropical cycles of heat and rain. Errant movement -- a city crew digging, a slash-and-burn farmer plowing with a sharpened stick, a child exploring -- or age alone detonates them. That long-ago war lives on, even in the new century.

Between mid-1988 and mid-1991, demolition teams exploded more than 40,000 bombs in the Solomons. The head of the nation's bomb disposal unit noted in 1989, "Hell's Point (an ammunition dump near the airport) alone will take twenty to twenty-five years to clear."

Today's incessant rain, this freezing torrential downpour, reminds me that only death or rain can quiet the noise of battle. I think of Robert Leckie and John Hersey in those Guadalcanal foxholes, buried to their thighs in muck. A foxhole easily can become a boggy crypt.

Guadalcanal precipitated change for allies, Solomons

For the allies, Guadalcanal marked a turning point: victory here put the allies on the offense. To Solomon Islanders, it brought both liberation and the beginning of monumental changes in their country and their traditional way of life.

The Solomon Islands capital city of Honiara didn't exist on August 7, 1942, when the First Marine Division splashed ashore near Point Cruz. Marines swept past sleepy clusters of thatched huts, now swallowed up by Honiara--Tasimboko, Mataniko, Kukum. They captured a Japanese air strip and named it Henderson Field to honor an American pilot shot down over Midway Island. They bivouacked in coconut plantations and at jungle's edge.

For months America clung to Henderson as the Japanese clawed at its perimeter. Daily bombing and nightly shelling threatened a tenuous hold. Rain, steamy heat, malaria, and dysentery battered both armies. The battle dragged on for six months. It ended in February 1943, when Japan withdrew 10,652 debilitated, starving men from Cape Esperance, twenty-one miles west of Point Cruz. More than 7,000 Americans and 30,000 Japanese died fighting for Guadalcanal. Allied victory ended Japan's unimpeded advance on Australia. From here, the Pacific war marched slowly northward --first to Rendova and New Georgia, then beyond the Solomons to Rabaul, Tarawa, Guam, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and finally, in 1945, to Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

War memorials honor courage -- whether you're pacifist or warrior

On the long ride from Lumbaria Island to Ughele, the immediacy of Chief Willie's war stories intrigues me. Ughele has no violence--and thus no jail--no reason for war to live on in the nightly story-telling. Unless even pastoral men need a daily shot of violence, much like we Americans need the evening news and our action movies, to remind us peace is preferable to war. Maybe it's that tales of individual daring and cataclysmic battles thrive in oral history. After all, raids by pre-Christian headhunters, confrontations with missionaries, clashes with British colonials also live on in the nightly stories. In an oral society, history has no newspapers, no library archives. It breathes anew with each day's retelling.

Solomon Islanders believe themselves uniquely tied by the war to America. The feeling isn't mutual. Unlike residents of other U.S. battlegrounds in Europe, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and the Philip-pines, Solomon Islanders never entered America's continuing consciousness. We never bonded through massive post-war occupation or aid, through immigration or intermarriage.

In America, the Solomons war is no more than a bitter-sweet memory. For those who fought there, war may merit occasional reflection, like thumbing through an old photo album, then consigning it again to the mementos box. For those whose only tie is a father--or now, grandfather--who fought there, of what meaning is today's Solomons?

My generation's war was Viet Nam, but I'm a conscientious objector. I should be repulsed by Chief Willie's stories, but, somehow, they fascinate me. It's a dissonance that grew, ironically, from my Peace Corps service. As a volunteer in the mid-60s, I taught in Tacloban City, Leyte--near where General Douglas MacArthur, kept his promise to the Philippines when he said, "I shall return." Two of my fellow teachers survived the Bataan Death March and the prison camp horrors that followed. In the U.S., we measure the atrocities in terms of the 11,500 Americans captured on Bataan. We Americans forget--or never knew--that 65,000 Filipinos suffered the same fate. My co-workers' sober tales brought that infamous story to life.

In the late 70s, while living on Guadalcanal, my wife and I also supervised volunteers in the Gilbert Islands. I spent many a day poking through the detritus of Japanese battle bunkers on Tarawa, site of a bloody Marine landing.

Good men died in all those places. Others survived unspeakable horrors. One thing is clear: one doesn't dishonor pacifism by honoring the individual courage that war demands.

World War 2 liberated the Solomons and the Gilberts from Japanese oppression and paved the way for the death of British colonialism. Thus, I, too, sent money to the Guadalcanal-Solomon Islands War Memorial Foundation. Today, tourists can also visit official war sites on Guadalcanal: a granite and marble American memorial on Skyline ridge, a larger-than-life bronze at Rove police station of Sir Jacob Vouza, a U.S. memorial on Bloody Ridge, and the rebuilt wooden control tower that peers over Henderson Field like a 1940s forest fire-watcher's tower. All were dedicated in three busy days beginning August 7, 1992, exactly fifty years after the U.S. Marine landing.

Perhaps these physical memorials will give a few inquisitive Americans a new sense of their own history, or an inkling of how profoundly another nation holds America in its memory.

And what of my father's war?

In Ughele, I come to envy Chief Willie's living memories of his father, who has been dead for several years. My father, too, fought in World War 2, but he wasn't a storyteller. He died in a car accident in 1961, killed by a drunk driver. He never said a word about the war, not to his four kids. The Marshall family has no war stories.

We have a photo of Dad's H Company, 255th Infantry, taken in basic training at Ft. Hood, Texas. He sailed from New York on November 25, 1944--my third birthday. Two weeks later, December 8, he landed at Marseille, one more private in the 63rd Division, 7th Army.

|

|

Terry Marshall collection. Private First Class Charles Marshall, 1944. |

My father printed his personal war history neatly on a single "service record" page in the Armed Services Memorial Edition of Miller's The Complete History of World War II, as if the book were the family Bible. He left the briefest of records:

"Committed (to battle) Dec 23, '44.

"Entered Germany, Mar 15, '45.

"125 consecutive days on line.

"Relieved at 20 km from Munich, May 7.

"War ended in Germany.

"Sailed from Bremer Haven, Germany 12 Mar 46. Arrived N.Y. 23 Mar '46 aboard U.S.S. Victory Eufala. Released from service April 1, 1946, Ft. Lewis, Wash."

The Solomons campaign had ended long before PFC Charles Homer Marshall sailed for Europe. In the Pacific, Saipan and Guam had fallen. American B-29s had bombed Tokyo.

General Alexander Patch, commander on Guadalcanal when the Japanese fled in February 1943, now commanded America's 7th Army in France, one component of a massive multi-fronted push through the winter of 1944-45 into Germany. My father joined Patch's command two days before Christmas 1944 as the Battle of the Bulge raged to the north of Patch's troops.

Chief Willie's father, in loincloth and with captured Japanese weapons, fought in the jungle forest of his homeland. Through his son, his war exploits live on.

My father? His story must be imagined, conjured up from the reams that detail the sweep into Germany that bitter winter. Besides Miller's History, my father left his family a Veterans of Foreign Wars book, Pictorial History of World War II, and Bill Mauldin's Up Front.

Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, but my father remained in Germany for nearly a year. Did he, like Col. George Tuck on Guadalcanal, take time to meet the "natives," to fashion a bit of the familiar out of the alien environment into which he had been thrust?

I'll never know. Chief Willie's canoe took me only as far as Lumbaria and Munda, into the Pacific war. Germany lies beyond a different ocean. I suspect my father's war was more akin to that of Bill Mauldin's Willie and Joe than to Chief Willie's stories. Maybe we don't need an oral account to keep my father's war alive. He left us Mauldin's cartoons.

War weaves a new social fabric

On another sleepless night in Ughele, I struggle to reconcile my mishmash of images. War transformed the Solomons, even remote Rendova. Tens of thousands of troops swarmed islands occupied by tens, or at most, a few hundred villagers. Giant machines carved roads. Vehicles belched across the islands. Hundreds of islanders poured into Guadalcanal to work as stevedores and laborers. A city sprouted. Goods flowed. The invasion trampled existing social patterns.

American soldiers discovered that war, even on bloody Guadalcanal, could be other than one deadly charge after another into the breach. Some soldiers manned desks. They requisitioned provisions, cut orders, drafted reports. Others cooked meals, built roads, hauled supplies, handled mail or repaired planes and tanks and jeeps. Like George Tuck, they played basketball, explored, tended gardens, jawed for hours over homemade hooch, shot craps. They befriended Solomon Islanders, gave them food and clothing, exchanged stories and trinkets.

During World War 2, American soldiers saw precious few women in the Solomons. Most were safely hidden in the hills. GIs took no wives from the Solomons, visited no prostitutes, left behind no children--as they did in Australia and New Zealand, on the European front, in Japan, Okinawa, Guam, the Philippines, later Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines again. Maybe that's one reason Solomon Islanders so openly welcome Americans.

Jonathan Fifi'i, a Solomon Islander who worked in the labor corps on Guadalcanal, recalls in The Big Death: Solomon Islanders Remember World War II his first impressions of Americans:

They asked us to come inside their houses . . . what they called 'tents'. Big pieces of canvas. They invited us inside, and when we were inside, we could sit on their beds. We got inside and they gave us their glasses so we could drink out of them too. They gave us plates and we ate with their own spoons. This was the first we had seen of that kind of thing.

Early in 1943, black American soldiers landed on Guadalcanal. Many were laborers, but some black units went on to fight in New Georgia. They left an indelible heritage. Fifi'i writes:

Our bodies were the same. Some of them were really black, just like the people from Choiseul and the people from the Shortland Islands. . . But regardless, they were really great people! Any kind of thing that the whites did, they could do it too. They knew how to do carpentry, and they knew how to write. And they were the people that we worked together with.

Fifi'i spent three years in prison after the war for "acts of sedition"--he sought to organize his people against colonial domination--then went on to become a member of the Solomon Islands parliament. Many Solomon Islanders resented British rule before the war, but it was the war that galvanized them. Fifi'i recalled how Americans encouraged him:

They told us, "if you do it, they will lock you up in jail, they will tie you up, they'll shoot you. But you can't be afraid because you're strong. You must stand up and look them in the eye, be strong and big, and break the ties holding you to the whites. That's what we are telling you." And we were not afraid, and we did it.

Thirty-five years later, in 1978, Fifi'i took me to a meeting of headmen of the isolated Kwaio, the last pagan tribe in the Solomons, in the mountains of his native Malatia. He wanted Peace Corps volunteers to help run a new Kwaio culture center, but the Kwaio made such decisions only by consensus. We negotiated in a leaf hut near their proposed center. The elders filled the hut, three dozen bare-chested, sinewy mountain men in loin cloths, hunkering on the dirt floor, puffing home-made pipes. I spoke Pidgin; Jonathan translated into Kwaio. They grilled me: "What will they do, these Peace Corps?" one man asked. Others chimed in: "What do they eat? Will they live in a Kwaio house?" Must we pay them? We have no money. "

For three hours we met, rehashing some questions five times. Finally, one old man stood, and announced in Kwaio, "We do not understand this Peace Corps. But you represent America, not Britain. We trust you. We want a Peace Corps."

Change comes also to Ughele

Chief Willie knows his Solomon Islands war history. He knows also how deceptive the peace and quiet of village life can be--especially on Rendova. He realizes a new era of change confronts Ughele, and all Solomons.

No multinationals tend coconut plantations on Rendova. It has no tuna cannery, no gold mine, no government center. But virgin rainforest covers the island. Logging flourishes. By late December, in my fourth week in Ughele, the discordant snarls of bulldozer and chainsaw shatter the silence. "Progress" chews a road closer and closer to the village.

|

|

Terry Marshall. Typical thatch house in Ughele, Rendova, Solomon Islands. |

On New Year's Eve, at the home of a local big-man, I meet a Chinese Malaysian who manages the logging company. He will extend the new logging road through the village. "We will rebuild Ughele," he boasts. New Ughele will be a modern town, laid out neatly in rows. The old, familiar huts will be lost, yes, but corrugated iron and lumber last longer than thatch, and they are more handsome, he tells me.

Two days into 1992, trees topple in the jungle behind the school. The logging company will carve a new soccer field for the kids, Chief Willie promises. He doesn't mention the road.

Ughele earns a royalty payment for each tree logged. Every village member, from child to adult, owns an equal share. The village has bought its own ship from Japan--not a small boat, but an inter-island cargo ship. It will ply the Western Solomons, exporting logs and importing supplies to Ughele and neighboring islands, mining logging royalties for further profit.

A Solomon Islands crew has flown to Japan to sail the ship to the Solomons. Each night Pastor tracks its progress on a short-wave radio. It will be here by Christmas, he reports. Then, New Years. Rough seas, further delay: mid-January.

Even in conservative Ughele, age-old prohibitions seem under attack. Willie had explained local beliefs so we visitors wouldn't violate custom: no alcohol, public smoking, pre-marital sex. A holy Sabbath, modest dress, late-night quiet.

But at Christmas, youths flock home, some from school, others from jobs or from hanging out in Honiara. Teenagers roam 'til dawn. They flaunt accouterments of the city: gaudy T-shirts, sun-glasses, short skirts. And though most Solomon Islanders go barefoot, a few youths sport athletic shoes. They swap cassettes and with battery-run boom boxes, assault the village with the ear-splitting cacophony my pre-teen son hammers me with in Denver. All night sing-sings assail our sleep. Cigarette butts--some bearing lipstick stains--smolder along the main path.

No one sells liquor in Ughele, but in the wee hours, across the foot-bridge to Kombi, a "barrio" at one end of the village, traveled young men sing in drunken revelry. A few daring girls join them. Beer comes from Munda or Noro, where construction of a tuna cannery has produced a boom town. In calm sea, either source is four hours round-trip by motorized canoe.

A Saturday stroll catches backsliders at home rather than in church, wash being laid out to dry, cooking fires burning. One of Willie's teen-age daughters asks if I want her to find a village woman to sleep with me. A local girl has moved in with a Peace Corps stud.

Chief Willie overlooks the transgressions. They're too prevalent, and he knows no village sea wall can keep them out. Change is part of Solomon Islands history. He chooses to work with it, to try to nudge it in directions that foster his vision of the future.

"War remains always with us"

Over the years, correspondence with friends in the Solomons trickles in. In one letter, a friend writes in 1995, "Things are well in Honiara. I hear nothing of Ugehle." By chance my wife and daughter meet a Solomon Islander in Hawaii in 2001. He sent an occasional e-mail. At last count, he had a job, and didn't plan to go home: the economy's failing, the opportunities few. He was right. Government mismanagement and corruption were rampant. As the economy declined, so did relations between the many Malaitans on Guadalcanal, and Guadalcanal natives. Skirmishes broke out in the late 1990s, then escalated into armed battles between the Malaita Eagle Force and the Istabu Freedom Movement. In June 2000, a coup d'état overthrew the government.

The root cause: Honiara's mushrooming growth. Founded at Point Cruz in 1942, it has grown to 45,498, a tenth of the country's population. (The second largest city in the country is Gizo, population 5,984.) Islanders swarmed into the capital city--most of them Malaitans, took jobs in government and private industry, bought up and/or squatted on traditional lands.

The Twenty-First Century saw armed ruffians terrorize Honiara--stores looted, innocents accosted, robbed, beaten, several murdered. Thousands of Malaitans returned to their home island. Expats fled. The export industries--palm oil, copra, logging, tuna fishing and canning--screeched to a halt. Local businesses closed. Tourism died. National debt skyrocketed. The Peace Corps withdrew its volunteers in June 2000. They have not returned.

The warring parties signed a peace accord in October 2000, and the nation regained a modicum of order. But violence continued. Several government men were assassinated. In July 2003, Australia sent in a force of 1,750 troops to help local police restore law and order: the first influx of foreign soldiers into the Solomons since World War 2. An additional 500 men from Fiji, Tonga, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea joined them.

In August 2003, as if to reinforce Guadalcanal's image of a land facing never-ending war, workers discovered a World War 2 cache of more than 100 live 75mm shells in central Honiara. Three years later, in April 2006, violence erupted again: rioters burned Honiara's Chinatown business district to the ground. More than a thousand Chinese, many of them life-time residents, fled the country. As of November 2009, Aussie occupation continues, supplemented by a contingent of expat civil servants trying to revamp the corruption-plagued ministries. As our friend puts it, "Me fella happy too much long oloketa RAMSI -- we are very pleased with the Regional Assistant Mission to SI," because it is once again safe to go for a stroll at 7 in the evening -- not like it was during the conflict.

Law and order have been restored. The economy is recovering. Tendrils of American and Japanese tourism send out tentative new shoots. But logging--now fifty percent of the nation's exports--far outpaces reforestation and threatens the delicate ecosystem.

In the capital city, tension mounts between Solomon Islanders and Aussies. In September 2006, the prime minister declared the Australian high commissioner (ambassador) persona non grata and expelled him for meddling in local politics. Islanders grumble about high-living Aussies. Prostitution has increased. A January 2007 e-mail from the "Honiara Society for Outing Unfaithful Expatriates" announced its intent to eliminate marital infidelity by expat ministry officials living in Honiara.

In Ughele? Who knows. Ughele has no e-mail, no newspaper. Australia says the danger lies in Honiara and rural Guadalcanal. It warns its citizens to defer travel to the Solomons. That means everywhere: all legal access to the Solomons begins in Honiara.

I suspect life goes on in Ughele much as before. Residents grow their own food, catch fish, rebuild their houses with thatch and hand-made twine. This new war, this civil war, becomes another topic in the nightly talk-talk

I imagine Chief Willie shaking his head, wondering about the men of Guadalcanal and Malaita. "That's life in Solomon Islands," he might say. "War remains always with us."

"By Canoe into My Father's War" first appeared in Ecotone 2:2 (Spring 2007), www.ecotonejournal.com. It has been edited and updated for the web.

The Whole World Guide

Love the ideas and language learning tips here in our website?

Want to learn more about the Walkabout method? Buy your own copy of

The Whole World Guide to Language Learning:

How to live and learn any foreign language.

This book is chock full of ideas on how to use Walkabout language learning. It has sample lesson plans as well as language learning drills and practice tips. Order your copy today.

Return from "World War 2" to Culture Stories

Return to Your Language Guide home

Multicultural Literature

Check out the latest additions to our multicultural literature section: Multicultural Stories.This section offers both fictional and non-fictional stories and essays set in regions around the world.

You can read them on line for FREE.

The Whole World Guide

Love the ideas and language learning tips here in our website? Want to learn more about the Walkabout method? Buy your own copy of The Whole World Guide to Language Learning: How to live and learn any foreign language.

This book is chock full of ideas on how to use Walkabout language learning. It has sample lesson plans as well as language learning drills and practice tips. Order your copy today.

Then why not use the button below, to add us to your favorite bookmarking service?

Copyright© 2007-2016 YourLanguageGuide.com

All rights reserved.

Return to top

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.